The bankruptcy filing March 11 by the controlling entity of a proposed Central Oregon golf resort highlights the difficult times facing new projects.

Apart from the adverse economy, there are also growing questions if the area may be reaching a resort saturation point even if the overall business environment improves.

Thornburgh Resort Co. LLC filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in a move its legal representative said was designed to head off a scheduled April 8 foreclosure auction of acreage in the troubled project.

Altogether the resort planned for more than 1,900 acres around Cline Buttes west of Eagle Crest Resort would include 950 homes and 475 nightly rental units along with a golf course, originally to be designed by Arnold Palmer. The foreclosure auction would have applied to 1,350 acres of the project.

The bankruptcy filing lists 20 unsecured creditors with claims totaling more than $11 million. In October of 2010 the notice of default triggering the scheduled auction listed $12.1 million owned on a principal loan and related overdue interest and other charges.

Some observers believe that Thornburgh faced an uphill battle from the start, even in a better economy. Opposing conservation and other groups cited traffic impacts and the potential to affect private wells due to increased water use.

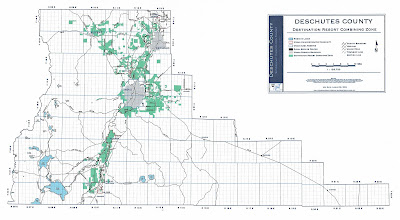

Thornburgh was also coming to market soon after several other newer resorts were already open or well on their way. These include Pronghorn Resort east of Hwy 97 between Bend and Redmond; Tetherow on Bend’s west side abutting the Broken Top community, which has a private golf course; Brasada Ranch near Powell Butte in Crook County; and the proposed Remington Ranch, also in Crook County between Redmond and Prineville.

Remington is also working its way through bankruptcy after completing a clubhouse facility and part of it’s planned golf course.

In its bankruptcy filing of January, 2010, Remington Ranch LLC listed claims of $12.4 million among its 20 largest creditors, with $5.3 million due a major infrastructure contractor. Remington officials have said they will complete nine holes of a golf course while in bankruptcy. But original plans called for three courses, 400 nightly units and 800 homesites on its nearly 2,100 acres.

Other resorts proposed in Crook County in the boom years were Hidden Canyon and Crossing Trails, neither of which has gained traction in the entitlement process. In 2008 Crook County repealed its resort map which has allowed the resorts, leaving plans for the projects uncertain. New investors for Brasada Ranch, Eagle Crest and Running Y

Perhaps in the best shape among new generation resorts is Brasada Ranch, which was purchased in late 2010 from the original developer, Jeld-Wen, by the Northfield Group with backing of Oaktree Capital. Jeld-Wen, founded as a door and window manufacturer in Gilchrist, also sold Eagle Crest and Running Y resort near Klamath Falls to Northfield. The 640-acre Pronghorn continues to operate its Nicklaus and Fazio courses while sales of developer homesites have slowed to a crawl as foreclosures and short sales accounted for much of the sales activity. The resort is permitted for 450 homes and 280 nightly lodging units.

Most lot sales at Pronghorn have a deed-restriction requirement for transfers of club memberships at the time of a lot sale. Pronghorn developers have valued the memberships at $115,000. Some foreclosed lots have been listed for sale below $30,000 with the warning that buyers must do their own due diligence regarding the membership requirement.

Tetherow has completed its clubhouse and 18-hole links style golf course designed by David McLay Kidd, highly praised for his work at Bandon Dunes on the Oregon Coast. After initial sales of more than 50 homesites, sales have ground to a halt since mid 2009, with only one sale in 2011 and none in 2010 according to member of the sales team. On approximately 700 acres, Tetherow was initially planned to include more than 379 homesites, the golf course and clubhouse and luxury hotel with spa, 56 lodge homes and 210 townhomes. Apart from the finished course and clubhouse plans are on hold as various investors and lenders have juggled ownership. About 66 acres would be designated for the hotel, lodge homes and townhomes.

As a strategy to spur sales activity beyond bare lots, current Tetherow managing developer Chris Van der Velde and investors have started construction on several homes of varied designs, size and price points. Van der Velde controls 68 home sites while Spring Capital, a Eugene investment group that also owns Salishan on the Oregon coast, has about 200 lots. A St.Louis group, Virtual Realty Enterprises LLC bought the proposed hotel and lodge home site. The complex multiple ownership of Tetherow has presented challenges to the county as well as owner-developers and their lenders. The county recently agreed to extend a deadline for construction of the proposed hotel and nightly lodging facilities, after earlier reducing the amount of a required bond to insure construction. The county has also previously loosened the time period for nightly lodging facilities at Pronghorn, citing economic conditions facing resort developers.

State regulations now require a ratio of 1:2.5 nightly rental units to owner occupied homes in new resorts. But Deschutes County’s resort code is more restrictive at 1:2, mandating one residence for each two homes. In an unlikely extreme case the county could take control of bond funds or drawn on a letter of credit posted by a developer who failed to perform by building nightly lodging. That would put the county in the position of moving ahead to build the lodging, something few counties would be willing to undertake.

In a situation involving Tetherow, the buyer of the lodging component of the resort threatened to sue the county if it began to draw on a letter of credit issued by the original developer.

New law will stiffen resort requirements

The problems with new projects have caused some, including county officials, to question if Central Oregon may be overbuilt with larger-scale resorts now in the pipeline joining those with established track records. However, resorts have been mainstays of Central Oregon’s critical tourism economy, not only bringing in visitor dollars but enticing new residents including many who start or bring businesses to the area. An emerging factor is a new state law that would prohibit new resorts within 24 miles of an urban growth boundary of cities with a population of more than 100,000, a threshold some estimates say could be reached by Bend in 8-10 years. The US Census estimated Bend’s population at 76,639 in 2010, below the 83,215 number given by the Population Research Center at Portland State University, which is the state-designated demographer. The legislation would in effect mean that future resorts would have to be built considerably farther away from population areas. A resort such as Tetherow, which abuts Bend’s southwest city limit, would not be possible at that time. Even as new resorts struggle to thrive, or just survive, several of the area’s older, established ones seem to be holding their own and some have expansion plans. Sunriver Resort and Black Butte Ranch are Central Oregon’s “legacy” resorts. Sunriver's development group, through Pine Forest Development LLC, have applied to build 925 homes on 617 acres it owns south of Sunriver’s Caldera Springs project and across from its private Crosswater golf community on the Deschutes River. Sunriver Resort Partnership LLC is also is the controlling owner of nearby Sunriver Resort, long-identified as the largest “dry side” destination resort in the Northwest appealing to vacation home owners and visitors seeking an escape from rainy areas along the I-5 corridor of Oregon and Washington. For the new project, known initially as Pine Forest, the developer has proposed contributing up to $3 million to construction of a waste treatment facility that would serve a larger area of the south county that has been plagued by excessive nitrates from septic systems. The payments would be indexed to sales of new homes and home sites. In exchange for the payments, House Bill 3347 in the Oregon legislature would require the county and state to remove deed restrictions requiring nightly lodging at the Sunriver group’s adjacent Caldera Springs project. Although Sunriver has applied to the county to build Pine Forest as a destination resort, the bill would enable the developers to instead build it mostly as a residential planned development with 25 percent of the units “designed to encourage and facilitate” nightly lodging. A provison of the legislation that would create a sanitary authority funded in part by developer payments has spurred objections from some residents who would be required to connect to the treatment system. The developers argue that the nitrate problems in the south county near the Deschutes River could eventually result in sanctions by federal and state authorities. Sunriver Resort, 17 miles south of Bend, was developed on 3,300 acres in the late 1960s by John Gray, also developer of Salishan on the Oregon coast and Skamania Lodge along the Columbia River in Washington. It is now managed by Lowe Development’s Destination Hotels and Resorts. The resort has three golf courses, the Sage Springs Spa, Meadows Lodge and a convention-meeting center. There are approximately 1,700 permanent residents in Sunriver’s 4,000 homes but in the peak summer season the population can expand to nearly 20,000. The retail village with a grocery, offices, restaurants and an ice rink is now owned by Salem-based Colson family interests and is undergoing extensive renovation.

Black Butte Ranch, eight miles west of Sisters, also has considerable cachet among established sunny-side Northwest resorts. Developed in the early 1970s by a real estate subsidiary of the Brooks-Scanlon logging company, Black Butte today is essentially “built-out” with approximately 1,250 homes and only 20 vacant lots. It has a mix of single family homes and condos-townhomes, many available for nightly lodging.

Eagle Crest built in the 1980s on 1,700 acres is also among the older established Central Oregon resorts, including three golf courses, a convention facility, nightly lodging and retail village. The infusion of capital by the Northfield Group, which also bought Brasada Ranch, will result in improved convention facilities and main lodge areas, the investment group has announced. The more than $15 million in taxes paid to Deschutes County by Sunriver in Fiscal 2008-2009 were more than double the combined payments by Black Butte Ranch and Eagle Crest. Inn of the 7th Mountain, adjacent to the Widgi Creek golf community, is another of the Bend area’s older resorts. After undergoing ownership changes and restructuring of the homeowners association, there are substantial improvements underway to condo and nightly lodging facilities. Mt Bachelor Village, another 1970s era resort and vacation home community within the Bend city limits on Century Drive, also has meeting facilities, condos and townhomes, many of them available for nightly rentals.

Related post: